FUTURE FOODS of RICHMOND

Climatologist Sonali McDermitt and PhD researcher Kat Morgan projected Richmond’s agriculture 1,000 years from now, when Gamma Cephei becomes the North Star. Their models predicted the ingredients future Virginians will cook with, including some southern staples like collards and black-eyed peas, but also kudzu and dandelion root.

The Secret Supper society worked with Chef Bryan Mclure and Sommelier Chauncey Jenkins to craft a tasting menu using those very foods. A speculative science experiment becomes a meal, offering a literal taste of the future.

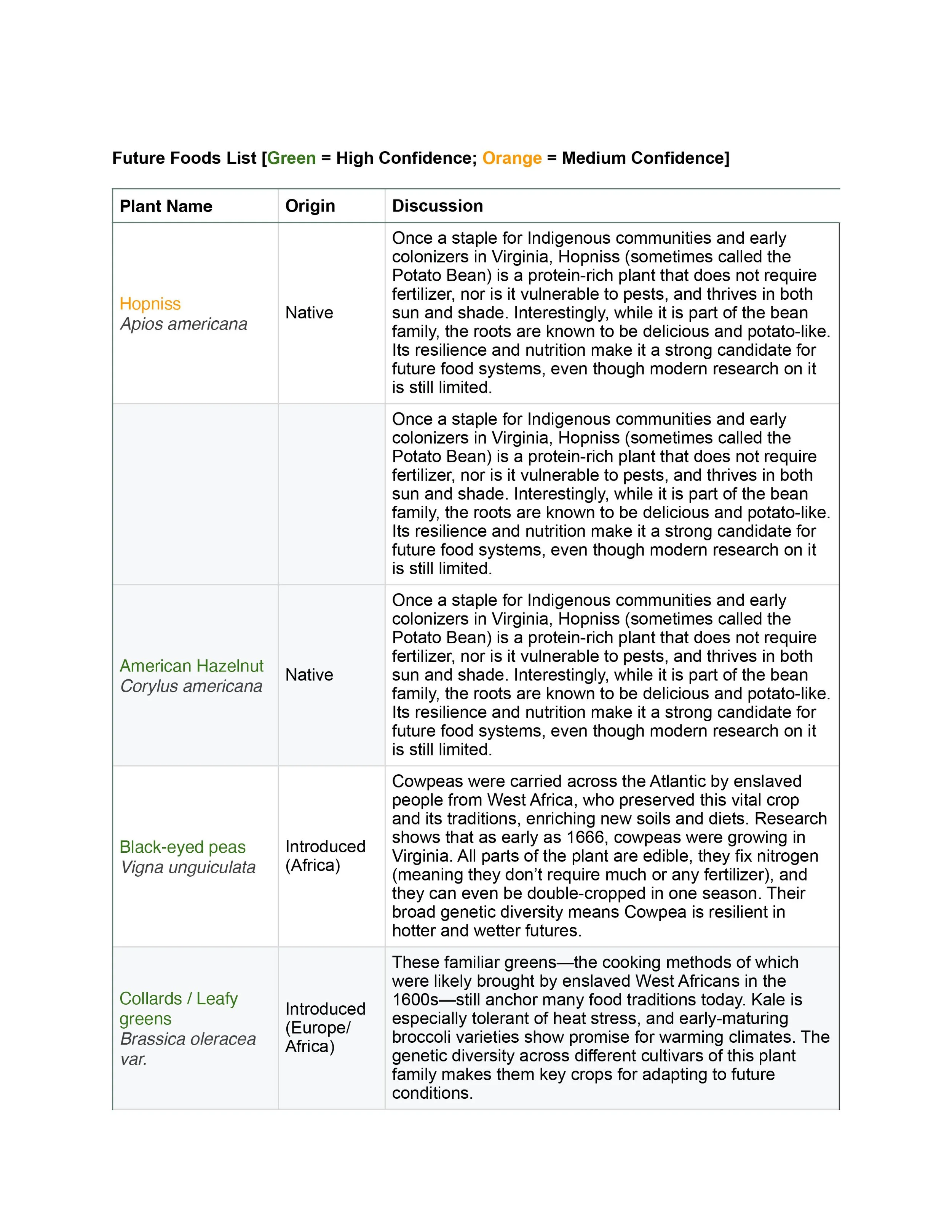

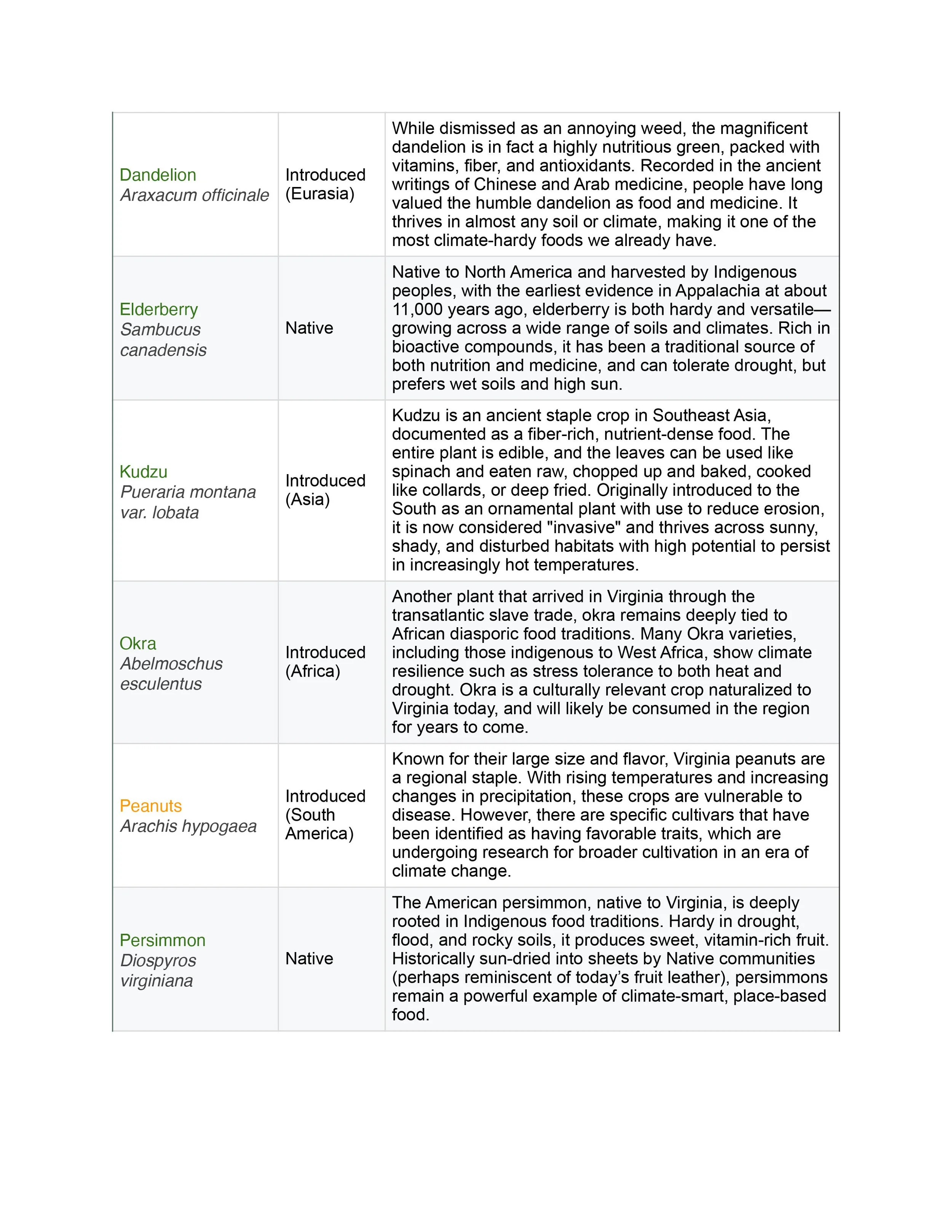

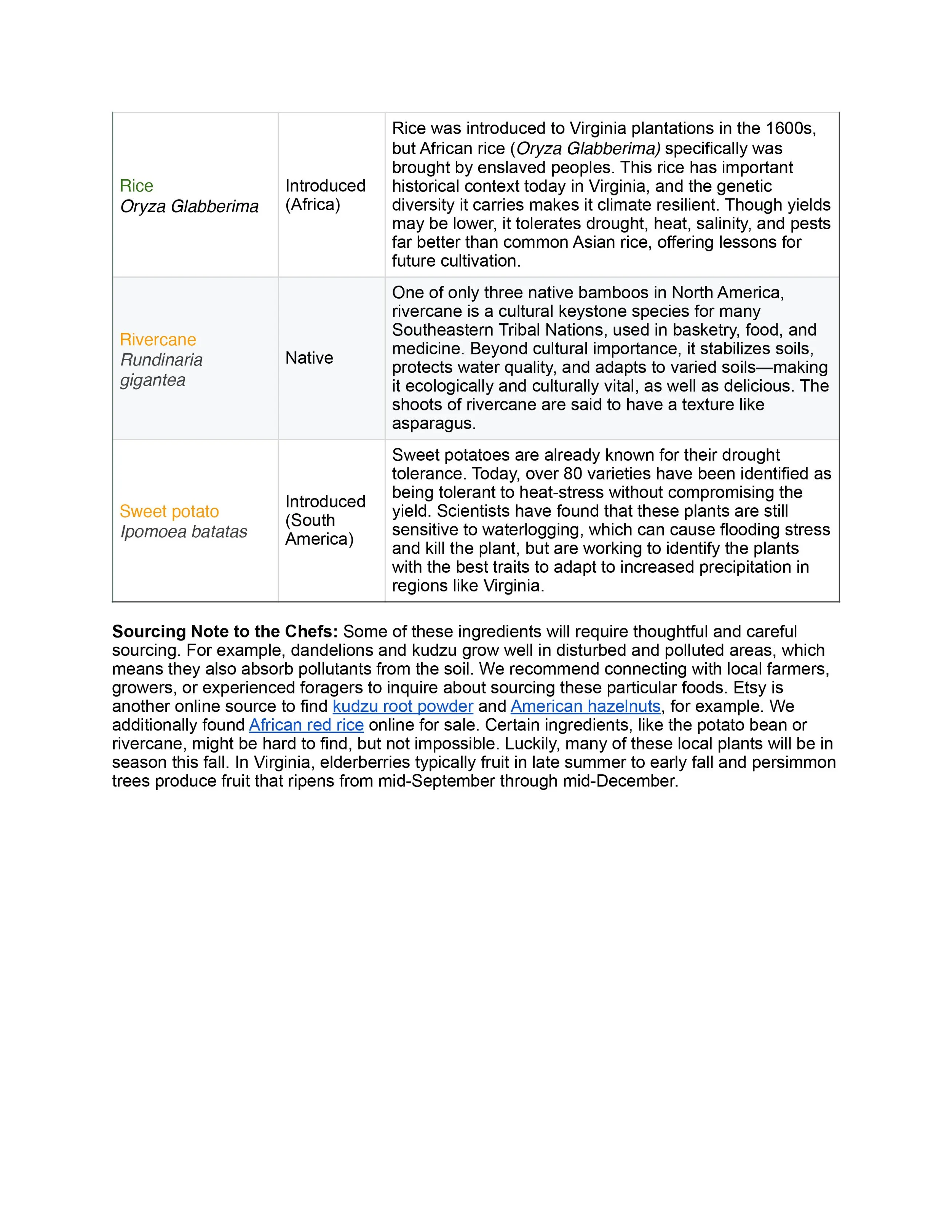

The Future Foods List captures viable ingredients in Richmond, VA, that 1000 years from now, folks in the area might be eating. This list embraces the complex history of each plant to prompt reflection on the cultural and environmental relevance of each food on the broader scale of time and foreground the role of historically uncelebrated people in the invention of future food cultures.

Historical Context:

The story of agriculture in Virginia is an ancient one. Long before the United States existed, a rich agricultural landscape thrived. The earliest evidence of agriculture in Virginia is associated with Indigenous Algonquin and Siouan-speaking people who have lived in the region as far back as 11,000 BCE, and practiced agriculture as early as 1000 BCE. By the early 1600s, European settlers landed on Virginia’s shores, immediately confronted by severe drought, harsh winters, and disease. According to the Library of Congress, “As the colonists searched for instant wealth, they neglected planting corn and other work necessary to make their colony self-sufficient.” In order to attract more colonists, the Virginia Company of London encouraged plantation settlements, offering any man able to pay his way to the continent 50 acres of land. In 1619, the first ship carrying enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia beginning 246 years of slavery in the United States, characterized by atrocious conditions of forced labor and violence. West African food traditions are deeply intertwined in foodways across cultural lines in Virginia today. As we look forward to shaping new cultural traditions focused on caring for future generations, we must not overlook the past, and the people and plants which led us to where we are today.

Climate projections:

To imagine alternative futures, we must first reckon with the state of our planet at present. Long-term climate data show that central Virginia is already substantially warmer and wetter than it was 200 years ago, and average seasonal and annual temperatures will continue to rise through mid-century. These changes include increasing inches of yearly rainfall, flood conditions, and the number of days exceeding 90 degrees Fahrenheit. These changes in temperature, precipitation, humidity, and soil characteristics can all affect crop growth. Using a variety of data, tools, and knowledge, we can begin to consider how these changes impact current food production and which plants will be able to adapt to and thrive in the future climate.

Food stressors in a changing climate:

The rising temperatures we anticipate in central Virginia will increase heat stress for crops, livestock, and workers, while warmer winters will make it difficult for crops to bloom and fruit. Increased precipitation and possible rising water tables also increase the risk of flash floods, water logging, and soil erosion. Pest, disease, and weed pressures, particularly from competitive insect species will also intensify in a warming planet. Together, these stressors threaten crop yields, regional food security, and agricultural livelihoods in Virginia. This isis why the specific crops we’ve selected not only have historical relevance to the region, but have a stronger likelihood of producing food for human consumption in the future. What makes the crops in the list stand out is their genetic diversity. In essence, plants and plant populations with plenty of traits have more means to adapt to, survive, and thrive in changing environmental conditions than plants that don’t, which unfortunately include many of our currently cultivated crops.

Importantly, many of the crops in this list are native to Virginia and/or grow well in the changing Virginian climate. Though you may not recognize them by name or taste, Indigenous peoples, colonizers, and folks of African descent ate them long before they fell out of our contemporary memory. Virginia’s agricultural history is complex and a difficult one, as notable crops in our list are of African origin as a result of the transatlantic slave trade, and forced labor of enslaved Africans and their descendants. Okra and black eyed peas are crops that came to America as a result of this historical legacy. Other plants on the list, like kudzu and dandelion, might make you scratch your head. Why would I eat weeds? Well, weeds are plants, just like the crops we grow for food, and are in fact, incredibly resilient and able to thrive under challenging conditions. As “weeds,” neither kudzu nor dandelion is native to the Americas, but they thrive in the Southeastern U.S., and are known to be nutritious and delicious.

1 https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/virginia-agriculture-portici-cultural-landscape-manassas.htm

2https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/little-ice-age-and-colonial-virginia-the/#:~:text=And%20as%20a%20result%20of,droughts%2C%20and%20particularly%20cold%20winters.

3https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/colonial-settlement-1600-1763/virginia-relations-with-native-americans/

4 https://www.nps.gov/articles/plantationsystem.htm

5 https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/arrival-of-the-first-africans-in-1619.htm

6 Shiflett, L. R. (2004). West African food traditions in Virginia foodways: A historical analysis of origins and survivals (Master’s thesis, East Tennessee State University). East Tennessee State University.

7 PRISM Climate Group. 2025. PRISM Climate Data. Oregon State University. http://prism.oregonstate.edu/.

8 Hoffman, J.S., S.G. McNulty, C. Brown, K.D. Dello, P.N. Knox, A. Lascurain, C. Mickalonis, G.T. Mitchum, L. Rivers III, M. Schaefer, G.P. Smith, J.S. Camp, and K.M. Wood, 2023: Ch. 22. Southeast. In: Fifth National Climate Assessment. Crimmins, A.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock, Eds. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH22

9 Hoffman et al., 2023